The Nation: As a Black Mother, My Parenting Is Always Political

Share

To care for, protect, and prepare our children for adulthood, black moms cannot merely accept the world as it is.

Read article in it’s entirety at TheNation.com…

By Dani McClain | March 27, 2019

Illustration by Edel Rodriguez.

When I was 7 or 8 years old, my mother would put on Whitney Houston’s “Greatest Love of All” every day before we left home for school and work, and we sang along from start to finish. Standing in the living room moments before we shrugged on our coats, we belted out lyrics about self-reliance and persistence, finding a kind of armor through song. We wrapped ourselves in the richness and power of Whitney’s voice, reaching for the high notes right along with her. I can’t remember how long this lasted, but I consider it a defining ritual of my childhood. She’s too young now, but I plan to do something similar with my daughter, Isobel, who is 2. Black children and their families need this. We need a kind of anthem, a melodic reminder to ourselves and each other that we are not who the wider world too often tells us we are: criminal, disposable, lazy, undeserving of health or peace or laughter.

This article is adapted from We Live for the We: The Political Power of Black Motherhood, by Dani McClain. Reprinted with permission from Bold Type Books, a division of the Hachette Book Group.

Black mothers like me know that motherhood is deeply political. Black women are more likely to die during pregnancy or birth than women of any other race. My own mother, who has never married and who worked full-time throughout my childhood, is a model for my own parenting, but culture-war messages from the left and the right tell us she fell short of maternal ideals. My grandmother, great-grandmother, aunts, and elders in the community supported my mother as she raised me. Their investment in me and in other children—some their blood relations, some not—demonstrated an ethic that we can all learn from. Sociologist Patricia Hill Collins has called this “other-mothering,” a system of care through which black mothers are accountable to and work on behalf of all black children in a particular community. “I tell my daughter all the time: We don’t live for the ‘I.’ We live for the ‘we,’” Cat Brooks, an organizer in Oakland, told me.

In addition to serving as other-mothers, we’ve had to fight for our right to bemothers. Prior to Emancipation, the child of an enslaved woman was someone else’s property. Slave owners routinely destabilized enslaved people’s lives, severing kinship structures rooted in marriage and blood ties; family as a concept became elastic and inclusive.

Because of this history, black women have had to inhabit a different understanding of motherhood in order to navigate American life. If we merely accepted the status quo and failed to challenge the forces that have kept black people and women oppressed, then we participated in our own and our children’s destruction. In recent years, this has become especially evident, as dozens of black women and men have had to stand before television cameras reminding the world that their recently slain children were in fact human beings, were loved and sources of joy. The mothers of those killed by police or vigilante violence embody every black mother’s deepest fears: that we will not be able to adequately protect our children from or prepare them for a world that has to be convinced of their worth. Many parents speak of feeling more fear and anxiety once they take responsibility for keeping another human alive and well. But black women especially know fear—how to live despite it and how to metabolize it for our children so that they’re not consumed by it.

In the fever dream that has been life in the United States since Donald Trump came to power, some of black women’s deepest fears have become more comprehensible to the broader society. No one has ever been able to guarantee safe passage into adulthood for their children, but nonblack parents with money, citizenship, and class status had a leg up on the rest of us. Now, even for many of them, the threats and uncertainty seem to multiply by the day. The Trump era has given those who may have previously felt invulnerable to the shifting tides of human fortune a wake-up call.

Family is often the first social institution to shape how we understand our identities and our politics. At a time when “Resist!” has for some become a national battle cry in response to the norms-trampling Trump administration, it’s critical to look at the messages communicated within our families and address hypocrisies or inconsistencies head on. Research suggests that white parents in particular need help seeing family as a source of political education, especially when it comes to passing on anti-racist values. A 2007 study in the Journal of Marriage and Family found that out of 17,000 families with kindergartners, parents of color are about three times more likely to discuss race than their white counterparts. Seventy-five percent of the white parents in the study never or almost never talked about race. According to research highlighted in Po Bronson and Ashley Merryman’s 2009 book, NurtureShock, white parents communicate messages that skin color doesn’t matter and that everyone is equal—messages that children know to be lies based on their own experiences even as early as infancy. When pressed, these parents often admit that they don’t know how to talk about race. Black mothers, on the other hand, are scared not of talk of race, but of the impact of racist oppression. We’re scared because we have no choice but to release our beloved creations into environments—doctors’ offices, hospitals, day-care facilities, playgrounds, schools—where white supremacy is often woven into the fabric of the institution, and is both consciously and unwittingly practiced by the people acting in loco parentis. Black mothers haven’t had the luxury of sticking our heads in the sand and hoping that our children learn about race and power as they go. Instead, we must act as a buffer and translator between them and the world, beginning from their earliest days.

The right to be a mother: Before Emancipation, enslaved women had no legal right to their children, and slave owners often severed kinship relations rooted in marriage or blood ties. (Library of Congress)

Iam the daughter of an unmarried black woman. I am now an unmarried black woman raising a girl. I didn’t grow up with my father at home. As has been the case since soon after her first birthday, my daughter isn’t either. I didn’t meet my father until I was in my early 20s. Our meeting was healing, but his absence hadn’t mattered in the ways that some people assumed it would. I grew up in a house in the suburbs, the same house where my mom and her sisters and their dad before them had grown up. My maternal grandmother had grown up around the corner. We had a big in-ground pool in the backyard, where I’d swim with my cousins and other neighborhood kids. I grew up playing soccer and riding horses and skiing, and on the few occasions that I was referred to jokingly as a “Cosby kid,” I knew what that meant: I was privileged, maybe even a little spoiled.

I always had a kind of unvarnished pride in my upbringing. None of the assumptions people seemed to have about families headed by “single mothers” applied to my life. As an only child, I was the focus of my mom’s attention and resources. That investment in my success and happiness was supplemented by the love, time, and money of other adults in our family, especially my maternal aunt, Pam, who lived with my mom and me from the time I was 7. Extended family was everything, and while the word “family” seemed to mean a mom and dad and siblings to some, to me it’s always meant aunts and uncles and cousins and grandparents and the neighborhood elders who watched you grow up.

Like me, my daughter is growing up without a dad at home, but the similarities in our experiences end there. My father lived across the country—he’d moved west before I was born to pursue a graduate degree—and we had no contact until I sought him out and initiated a conversation that led to us staying in touch for a few years. My daughter’s dad also lives in a different city, but he was by my side during her birth and cared for her daily during the first year of her life, while we were still together romantically, and before he relocated for a job. He visits her often and video-chats with her daily, and they have a relationship that I support and that brings us all joy. Our family is not unique in this. In 2013, a study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention corrected the misconception that black men disproportionately shirk their fatherly duties. Instead, black men are generally more likely than men of other races to read to, feed, bathe, and play with their young children on a daily basis, whether they live in the same home as the child or not. Relying on nonmarital birthrates to tell a story about parental involvement has built a false narrative. Just because a father isn’t married to his child’s mother doesn’t mean he’s an absent dad.

For my daughter’s dad and me, it’s not easy, but we work at it. For about six months after our breakup, we were in therapy to learn how to parent together despite our separation. I feel proud of us when I read a line from a 2008 study on co-parenting outside of marriage: “We conclude that parents’ ability to work together in rearing their common child across households helps keep nonresident fathers connected to their children and that programs aimed at improving parents’ ability to communicate may have benefits for children irrespective of whether the parents’ romantic relationship remains intact.” We created our own program with the coaching of a black woman who talked us through some painful periods and helped us put our goals and commitments on paper. Now here we are—making the road by walking.

My father and my daughter’s father are college-educated black men from middle-class families. They both grew up with their dads at home. At the time of their children’s births, they were gainfully employed or training to advance in a profession. They were not ripped away by death or by the criminal-justice system or by the Pull of the Streets™. But not all black single moms have such a benign family backstory. For every 100 black women in communities around the country, there are just 83 black men. “The remaining men—1.5 million of them—are, in a sense, missing,” The New York Times reported in April 2015, and incarceration and early death are to blame. There’s no comparable gender gap for white people. For every 100 white women, there are 99 white men. But nearly one in 12 black men between the ages of 25 and 54 are behind bars, a rate that’s five times that of nonblack men that age. The imbalance between free, living black boys and free, living black girls starts during their teen years and peaks in their 30s. (To be clear, black women are disproportionately incarcerated as well: One in 200 black women are behind bars, compared with one in 500 nonblack women.) These data help clarify why 30 percent of black families are headed by unmarried women, compared with 13 percent of American households overall.

G. Rosaline Preudhomme, a 73-year-old grandmother and organizer, helped passWashington, DC’s Initiative 71, which legalized marijuana. Preudhomme’s work seeks to address the systemic reasons for these “missing” black men. Fifty thousand people were behind bars for nonviolent drug offenses in 1980. By 1997, that number had jumped to more than 400,000, close to where it remains today. A study by the Economic Policy Institute found that the incarceration of parents takes a serious toll on their children; children of incarcerated parents suffer from more physical and mental health problems than those whose parents aren’t behind bars. Still, Preudhomme notes, despite the tremendous pressure that punitive drug policies have put on black communities in the past 40 years, our families persist. That’s in part because black Americans have had a structure for organizing family life that predates the drug war and accommodates the absence or intermittent presence of parents. “It’s the resilient spirit of black women that has gotten us through these past 400 years of our family life always being disrupted,” Preudhomme says.

Seeking humanity: Black parents have often had to remind the world that their slain children were in fact human beings. From left: Constance Malcolm, Gwen Carr, Hawa Bah, and Iris Baez all lost sons to police violence. (Sipa via AP)

In taking a village-oriented approach to child-rearing, black Americans may be out of step with mainstream white, middle-class American culture, which became more centered on the nuclear family at the middle of the last century with the advent of mass suburbanization. But we’re fully in step with how the rest of the world has functioned throughout most of history. A body of research has determined that Western, educated, industrialized, rich, democratic countries, with their focus on the nuclear family, bring up children in what anthropologist David Lancy has called “a departure from all other human culture.” Most humans across time and space are “cooperative breeders” and depend on adult women and older children in the extended family and community to care for the young.

When I think about my own childhood growing up with my mom and my maternal aunt, the first words that come to mind are “calm” and “even-keeled.” In the decade before I left home for college, when the three of us lived together, I can remember only one or two times when there were raised voices or heavy silences. This is not to suggest that only men struggle with their tempers. But men are more often socialized to believe that explosive anger and a pouty retreat into themselves are appropriate ways to communicate. I grew up never threatened with “wait till your father gets home,” never seeing one adult’s needs prioritized over another’s. I saw two adults treating each other with love, respect, and humor. I saw that it was possible to be a whole, healthy adult without marriage and, in my aunt’s case, without biological children of one’s own. Throughout my 30s, I was sympathetic, but somewhat baffled, as I watched some of my women friends struggle to make peace with their unmarried, unpartnered status. Many of them seemed to feel that kids were unlikely, since no partner was in sight, but their predicaments just looked to me like another way to do life. Because of my own upbringing, I felt liberated from the assumption that marriage and mothering must go together. Mainstream culture’s glorification of marriage leaves so many people feeling unnecessarily deflated and out of options when that type of union doesn’t materialize.

Last Father’s Day, I felt a swell of recognition when I saw black feminist writer Amber J. Phillips tweeting about her own father: “Because he opted out of being [a] parent, I was raised with the radical idea that I don’t actually need a patriarch in my home or life to be happy or feel a false sense of success.” In her 1987 essay, “The Meaning of Motherhood in Black Culture and Black Mother/Daughter Relationships,” Patricia Hill Collins writes that growing up in a household like mine, in which working mothers and extended-family support are common, creates a kind of domino effect. Generation after generation, black women reject ideas that the patriarchal family—and, by extension, patriarchy in the broader society—is normal. Collins suggests that slavery and the economic realities of Jim Crow made it hard for black families to create the separate, gender-based spheres of influence (father as economic provider and head of household, mother as nurturer and subordinate) that white America lauded as the ideal organization of family life. Instead, black girls grow up with a sense of empowerment and possibility that girls of other races don’t necessarily see modeled at home or in their communities. “Since Black mothers have a distinctive relationship to white patriarchy, they may be less likely to socialize their daughters into their proscribed roles as subordinates,” Collins writes.

Black families have developed a tradition of passing onto our children a culture that repels the forces of white supremacy and creates ample opportunities to question patriarchy. But unmarried black mothers and their daughters aren’t lauded for holding the keys to resisting patriarchal oppression. Our reliance on extended family networks and collective approaches to childcare, our rejection of the nuclear family as the only way to organize our lives, has been consistently derided throughout history. The dominant narrative is that we’re poor, draining public coffers, and so a blight on society. The safety zones that black parents have created, with leadership from black mothers, the places where we learn that we are not who the world tells us we are, have been criticized by everyone from Daniel Patrick Moynihan in the 1960s to the American Enterprise Institute’s W. Bradford Wilcox today.

Devoted dads: Black fathers are more likely than men of other races to read to, feed, bathe, and play with their young children on a daily basis, whether they live in the same home or not. (AP / David Goldman)

Those who promote marriage as social policy want us to believe that getting married will automatically lift poor people out of poverty. But poor plus poor does not somehow equal middle class. It means two poor adults raising poor kids and trying to figure out how to survive. Lost in the conversation is the impact that low-wage work has on black families. The question shouldn’t be whether we can put together two measly paychecks, but whether we as individuals can get paid a fair wage for the work that we do. In 2016, nearly 40 percent of black, female-headed households with children lived in poverty—meaning over 60 percent did not. Why don’t we talk about how that 60 percent is often doing just fine, or why that 40 percent is actually impoverished?

Governments aren’t equipped to understand all the pressures that low-income couples face, and they shouldn’t presume to meddle in romantic relationships. What governments are equipped to do is address poverty head on, by acknowledging and supporting people’s economic and social rights. Social policies such as paid parental leave, universal child care, and universal health care would go a long way to alleviate the financial pressures that unmarried moms face. This kind of government intervention is why a single mother and her child in Denmark are no more likely to be poor than a married mother and her child.

But the complex story of family formation and black mothering isn’t only about beating back stigma and correcting falsehoods; the psychic and emotional impact of leading households on our own is often ignored. I’ve been guilty of this myself. In writing about black women and marriage in the past, I’ve failed to acknowledge that some of us actually aspire to the narratives of being chosen, of living happily ever after. Yes, it’s important that we can and do successfully raise children without steady, committed romantic partners. But can we also note how depressing it is that we so often have to? There’s a reason some black women were excited when finally, after 12 seasons of the franchise, there was a blackBachelorette. Some of us want love, marriage, and a baby carriage in exactly that order, and preferably with black men. It’s important to acknowledge how it feels when those desires are often out of reach for us in a way they’re just not for other women.

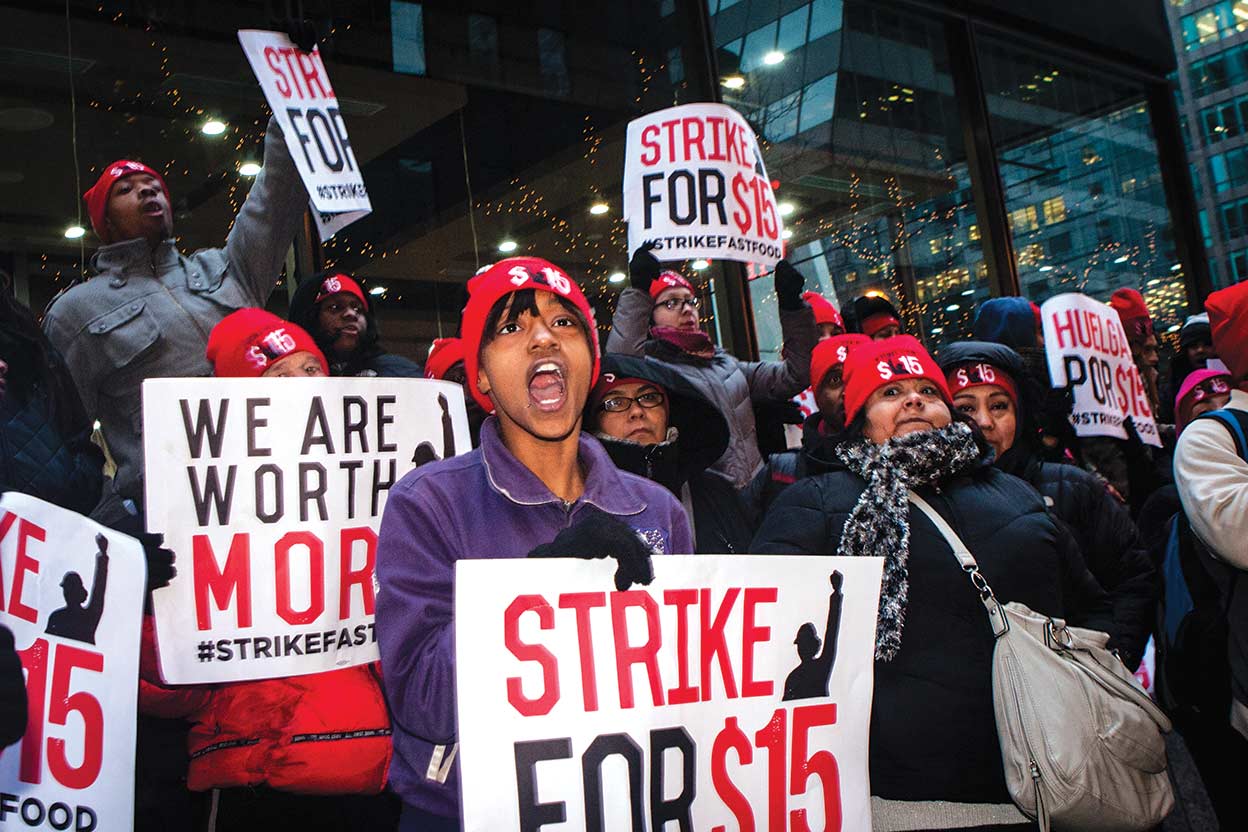

Poverty’s true causes: Lost in the conversation about single parenthood and poverty is the impact of low-wage work on black families. No wonder so many Fight for $15 leaders are black women.

Add to the existential angst the day-to-day responsibility of being in charge. Even with family help and enough money to pay for childcare, it’s exhausting to be the sole adult responsible for cooking, bathing, reading, playing, and cleaning on those days or in those stretches of hours when you’re going it alone. I never take it for granted that I was 100 percent certain I wanted to be a mother when I had my daughter. I can’t imagine giving mothering the energy it demands and deserves if I had come into this reluctantly, especially now that it’s often just the two of us. I enjoy the work of mothering and don’t often feel like I’m going through the motions or putting on a brave face, but there have been times when my spirit has flagged under the weight. I’m reminded of those times, the moments I’ve blinked back tears, when I read asha bandele’s memoir, Something Like Beautiful, about raising her daughter while her husband was incarcerated and then deported. She writes: “I told myself if I cried I was setting a bad example for my daughter. Others told me the very same thing. Told me never to be a victim, Black women are not victims and we are not weak…. In the post-welfare-reform days of the alpha mom, I was clear that being a victim, showing any weakness, was punishable by complete isolation and total loss of respect. I was a mother, a single mother, a single Black mother. I was part of a tradition of women who do not bend and who do not break. This is what I said, this is how I now defined myself. As someone with no room for error.”

I see little room for error in my own life. I have to guard against letting parenting become one more place I practice perfectionism. There are so many reasons to try to do it as close to perfectly as possible, since the mainstream conversation tells me that as both an unmarried mom and the child of an unmarried mom, I’m incapable of being or raising a successful, well-adjusted person. Even though I have known since childhood how mean-spirited and hollow that conversation is, I’m still affected by the stigma. As I get older, I can also see the danger in being too defensive, in disproving others’ assumptions before I honestly explore my own nuanced truths. In 2007, artist Meshell Ndegeocello released an album called The World Has Made Me the Man of My Dreams. That album’s title reminds me that learning to navigate an often-inhospitable world on one’s own and with the help of relatives and friends can make us into our own rock-solid protectors. Partnership with a man can begin to feel unnecessary: nice when it comes along, but not a must for survival or happiness. This strength can be a source of pride, but it can also be reason to grieve when one starts to think about all the structural and historical reasons that black women have had to be so independent, and black men have often been unavailable or unwilling to offer meaningful help.

It’s a February day, and Is and I are at the playground. I push her on the swing and notice that she can’t take her eyes off the next swing over, where a dad is pushing his daughter. I think to myself: I know that feeling. That “Why don’t I have that?” feeling. That “Where’s my dad?” feeling. That “I want bigger, messier, gruffer, rougher, and sillier than Mom” feeling. But the truth is that I’m projecting. My child is a watcher; she’s super-nosy and could be thinking anything. She actually gets playground time with her dad, though not daily. But my mind goes there because I am still, at 39, processing my own feelings around abandonment and loss. I don’t want that for my daughter. I don’t want her to know that sense of longing. If she does, I want her to know that she can express it, put it out in the open. In my experience, the silence around an absence can do more harm than the absence itself. For Is and for me, the challenge is to find—to make—space where we can be vulnerable and acknowledge hurt without giving into the narrative that we are of and in a “broken family.” As we are, our family is perfectly whole.

Follow Us